Jerelle Kraus

Two and a Half Hours Alone With Nixon

No one would be more repelled by Donald Trump, the blustering bully exploding in plain sight, than Richard Nixon, the brooding depressive imploding behind closed doors. “He left,” Trump has said of Nixon. “I don’t leave.”

I remember Nixon’s exit. The presidential helicopter swooped down to land on the White House lawn. As the staccato of its engine and the whirling of its propeller blades slowed to a stop, Nixon and his wife, Pat, emerged from the White House and soberly walked to the chopper’s door, where the newly ex-president turned to face the cameras. Hunching up his shoulders, thrusting out his arms, and flashing a studied grin, the chastened Nixon posed as a human victory sign, as if to say, I might be the sole American president in history to resign, but goddamnit, I’ll do it in style.

On the day of Nixon’s 1974 exit, my style was restive San Francisco hippie. Riveted to the TV in my violet and orange den, my friends and I saw Marine One take off and thought Nixon would never again figure in our lives. Yet on a Monday morning in 1982, as I began my work day at The New York Times, he again figured in mine.

I was scanning the week’s schedule of Op-Ed essays when one byline jumped out: Richard Nixon. How dare he emerge from obscurity! How dare we publish that pariah! But Nixon’s text was timely and trenchant. It made the case for easing U.S.-U.S.S.R. relations at a moment when President Reagan’s refusal to summit with the Soviets had driven the War from Cold to frozen.

Trump is now inciting a Cold War with China, but Nixon knew Hot War. He eagerly volunteered for the Navy during World War II. Given a desk job, he asked to be sent to the combat zone, where he served four years. Trump explains that he, too, fights war: “If you have any guilt about not having gone to Vietnam,” he’s said, “we have our own Vietnam—it’s called the dating game.” Trump sees female genitals as “potential landmines” and tells us, “I feel like a very brave soldier.” 1

The stalemate in American-Soviet rapport became Nixon’s platform for plotting resurrection. His piece depicted three Soviet summits: “To celebrate agreements,” he wrote, Brezhnev “and I regularly clinked champagne glasses.” Yet Nixon cautioned: “This hard-headed détente is not a love affair.”2

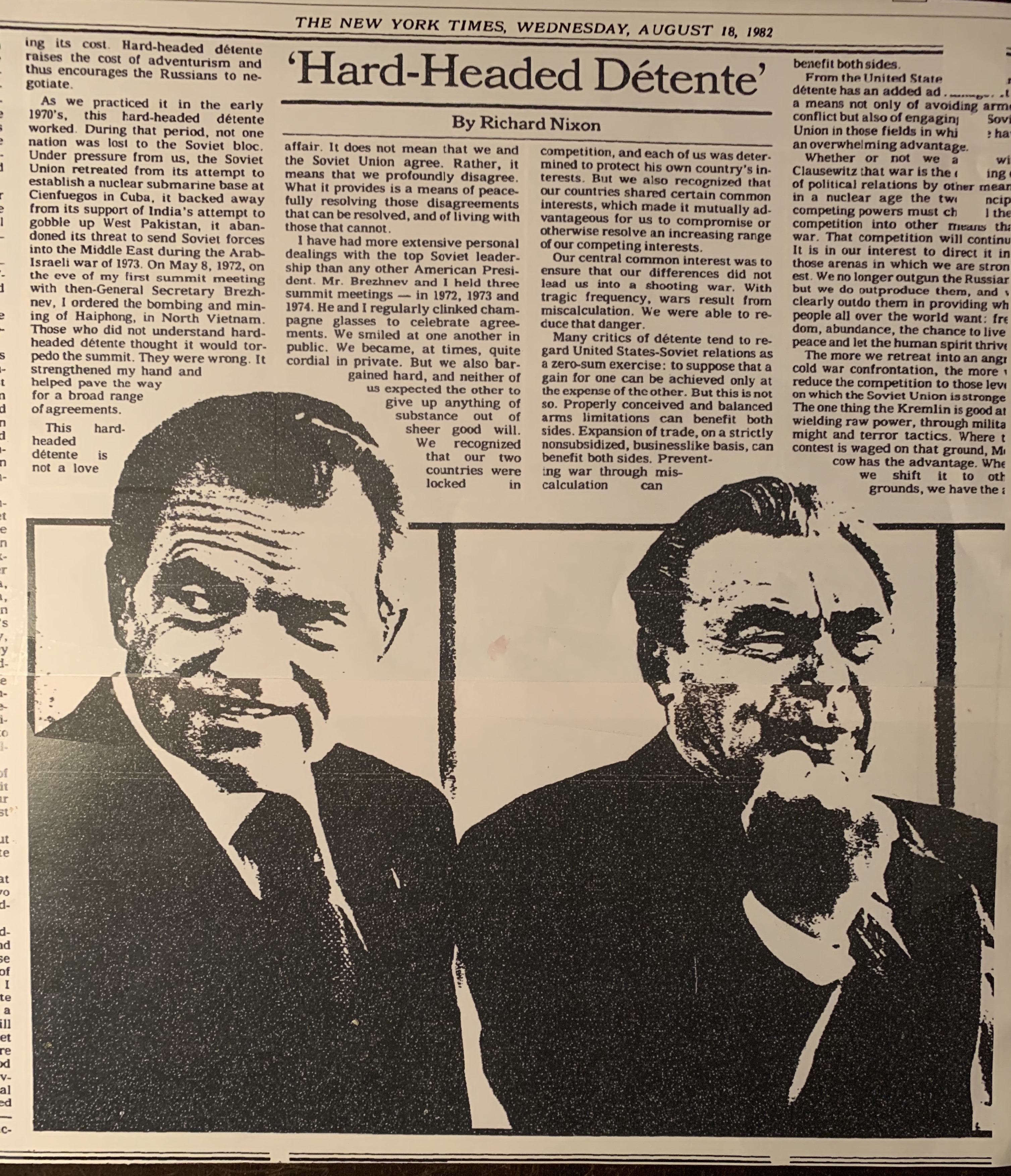

As Op-Ed art director, I needed to deliver an illustration for the essay. Normally, I published symbolic, rather than realistic, pictures. But the writer of this piece wasn’t another big-deal author, academic, or politician—it was Nixon. To spotlight that fact, I decided to run his portrait.

There could be no kicking Nixon around—he was the author, not the target—so commissioning a seasoned artist was out of the question; they’d all drawn Watergate imagery. To be safe, I would have to create the portrait myself.

I chose to show Nixon huddled with his Communist counterpart. Drawing lavishly browed Brezhnev was a breeze, but my loathing of Nixon ruined each of my attempts to draw him. In deadline despair, I converted photos of both men into high-contrast images, collaged them together and touched up the result, which I didn’t sign.

When I stepped onto the art department floor the next morning, I heard the relentless ringing of a phone, realized it was coming from my office, and—who could be so insistent?—ran to grasp the receiver.

“Miss Kraus? This is Ray Price, President Nixon’s press secretary. The president wants to speak to you.”

Then came the unmistakable voice of a peerless outlaw: “I admire your artwork for my Op-Ed piece today, and I’d like to have the original.”

I tightened my grip on the receiver. “Honestly, Mr. President, writers sometimes feel entitled, but the original belongs to the artist.”

“Well, I’d like to sign a copy of my memoirs to you.”

“Actually,” I replied, “Brezhnev made me a better offer.” (Brezhnev was dead.) Nixon didn’t laugh.

“Alright,” I said, skipping a beat, “I’ll bring it to you.” My impromptu offer was a wild shot in the dark. I wanted to meet the real-life monster under America’s bed.

"At 26 Federal Plaza," Nixon instructed, "find the only door with no name. Here's the code: three knocks, pause, one knock."

Ohmygod. I’ll be entering a cabal.

Nixon had long lurked in my life. When I was a child, my mother told me he’d demonized his Senate rival, Helen Gahagan Douglas, by saying she was “pink right down to her underwear.” Douglas retaliated, coining the nickname, “Tricky Dick.”

When Nixon was dispatching my fellow students to fight an unwinnable war, I planted myself on the Berkeley railroad tracks and waved a white flag in the path of Vietnam-bound troop trains. And when I art directed Ramparts magazine, we reported on Nixon’s sabotaging of the Vietnam peace talks and his covert carpet bombing of Cambodia, the first use of long-range heavy bombers. The air attacks, collectively codenamed Operation Menu, were dubbed Breakfast, Lunch, Snack, Dinner, Supper, and Dessert.3

That Nixon was a birthright Quaker had always offended me. He bore no resemblance to the pacifists I’d known on the pine benches of Pasadena Friends Meeting. A key Quaker principle holds that “there is that of God in every man.” Would I find godliness in Nixon?

The next morning, I found the unmarked door. When I’d knocked the cryptic signal, it opened a crack, and two blue-suited poker faces peered out. “I’m the Secret Service,” said one, pausing to point, “and so is he.” Without X-raying me or ransacking my purse, they ushered me inside and—poof!—disappeared.

I stood at the threshold of a vast chamber. Heavy grey drapes shrouded the walls. There was neither sound nor motion—a veritable tundra of frozen formality.

From a pole at the far end of the room, a single blush of color dangled limply. How odd: a flagpole emerging from a carpet. Next to the flag was a large, lawyerly desk from which a man slowly arose. His head tilted forward and his torso looked scooped out. As he strode forward, I saw incarnate what I’d struggled to draw—widow’s peak, jowls, extravagant ski-jump nose—atop shoulders that drooped like the flag. Nixon extended his hand.

“Good morning, Miss Kraus.”

“Hello, Mr. President.”

Then I delivered the only line I’d rehearsed: “You and I are both Californians, and we’re both Quakers. But I’ve remained a pacifist.”

In response to my cheeky opener, Nixon snapped into lecture mode to launch a lesson on Quakerism’s 17th-century founder, George Fox. “Fox insisted everyone was equal under God,” Nixon said. “He maintained that the king wasn’t divinely appointed.” The reason Nixon identified with a man who died in 1691 soon slipped out. “Fox,” he said, “was harshly and unjustly persecuted.”

As I listened to his lament, I sensed the elephant in the room—nobody visits Nixon—and felt a surge of responsibility. Nixon started the Environmental Protection Agency, he was the first president to visit Israel and Syria, and in a re-election landslide, he captured 49 states. Didn’t he deserve an audience?

I also remembered a 1972 Times article by Nixon’s psychiatrist, Arnold Hutschnecker, the only mental health professional known to have treated a man who became president.4 Dr. Hutschnecker said that Nixon had been “an emotionally deprived child” and recommended that would-be government leaders be vetted for mental, as well as physical, health. Had his recommendation been heeded, we very well might have been spared the spectacle of Trump.

Nixon's next tutorial was succinct realpolitik: “In today’s world, pacifism is not an option.” Instead of responding, I reached into my bag for the picture and placed it in his hands. I’d encased it in a five-dollar frame, which, in a nod to Brezhnev, I’d painted red. Now that illustration, albeit more elegantly framed, is preserved in Nixon’s presidential library. (Where shall we taxpayers build the Trump Presidential Library?)

Staring at the picture, Nixon smiled, squared his shoulders and straightened his lanky physique. After a decade of grotesque caricatures, here was proof of his prestige. In creating that proof, I’d seen beyond his besmirchment to his backbone. It was enough for him to cease orating and begin inquiring.

How long had I been at the Times? … Did I prefer New York or California? … What did an art director do? … What did I like to read? Time stretched out as he asked and I answered. Then came a surprise. “They’ve been real hard on me,” Nixon said, “but the Times is a damn good paper.” (The paper’s also been assessed by Trump, who’s said: “They don’t know how to write good.”)5

Nixon’s modest testament to the Times was in tune with his growing up. The son of a grade-school dropout, Nixon was a self-conscious square who skipped second grade. A bookworm who played the piano and violin, he had to turn down a tuition grant from Harvard to help in his father’s grocery. When Pat was seeing other guys and wouldn’t date him, Nixon became her constant driver. And when he was first urged to run for office, Nixon said, “I’m somebody who is nothing.”6

Trump says: “I alone can fix it.” He calls his fingers “long and beautiful,” adding: “as … are various other parts of my body.”

I soon noticed, on Nixon’s desk, the figurine of a dog. That must be—gasp—Checkers. The story rushed to mind: Nixon exploited Checkers, the family cocker spaniel, to defend himself against accusations he’d accepted illegal campaign contributions. Shrewdly conflating his financial corruption with the gift of a puppy to his daughters, Nixon told the television audience:

“The kids ... love the dog, and … regardless of what they say about it, we’re gonna keep it.”7

Thirty years later, Nixon held onto a miniature Checkers. But instead of facing its owner behind the desk, the spaniel statuette faced out—still performing, should anyone visit, public relations.

After Nixon lauded the Times, I had something to laud him for. “Congratulations on your wisdom in opening China,” I said. “I’ve been invited there on a cultural tour.”

“I’m going to China next week,” he said.

“Then why don’t I go with you!” I joked.

Nixon dropped his head, stunning me. For an awkward 30 seconds, he stared at the floor. Not only had my attempt at humor fallen flat, I’d committed a bona fide faux pas.

While time stood still, I flashed on what it would be like to tag along on his trip to the People’s Republic. No one got the reception Nixon enjoyed in China. Even the Times’ top editor got the standard factory tour.

Nixon finally raised his head. “You see, uh, uh …” he stammered. “Pat’s not going.”

It was extremely touching to see him struggle for words and then speak so frankly. Yet of all the reasons I’d be an unsuitable interloper in China, that one startled me.

As a lawyer, Nixon had been reluctant to work on divorce cases because he disliked frank sexual talk from women. Luckily for him, he missed out on tactless Trump. “If you need Viagra,” the pussy-grabbing president has said, “you’re probably with the wrong girl.”8

Changing the subject, Nixon reached for a copy of his 1,120-page memoir, RN, and generously inscribed it. Then he wrote a letter on his personal stationery, enclosed it in an envelope, tucked the envelope between the pages of RN and put the book in my hands. Then came a sudden camera flash. A blue-suited agent had appeared from nowhere to record the moment. When I glanced at my watch, I was astonished: 11:30. The Secret Service had left me alone with their boss for two and a half hours.

“I’m glad you came,” Nixon said as he accompanied me to the door.

While I walked to the subway, the Nixon of my last two-plus hours ricocheted off of the Nixon of my last two decades. And before long, Times Op-Ed artist Brad Holland’s conclusion about Nixon would echo my experience.

Holland, whom The Washington Post hailed as “the undisputed star of American illustration,”9 is the rare illustrator whose pictures carry such human depth—critics liken him to Goya—that any one of them can dramatize myriad manuscripts.

Holland’s images of the ’70s lashed out at Nixon. But as the Watergate saga dragged on, his drawings grew increasingly sympathetic. “I’m afraid I saw in Nixon many of the flaws I fear in myself,” Holland told me. “By the day he resigned I’d come to feel an odd admiration for the man. He seemed to be one of those perversely brave individuals who, in spite of their need to be admired, are willing to go through life without being understood.”

I found no godliness in Nixon, and he didn't charm me into forgiving his atrocities. But to draw him now, I'd need gobs of colors, bundles of brushes—and no deadline.

1 https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Donald_Trump. ↑

2 Richard Nixon, “Hard-Headed Détente,” The New York Times, 18 August 1982. ↑

3 “Operation Menu,” Wikipedia, last edited 25 March 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Menu#Breakfast_to Dessert. ↑

4 Erica Goode, “Arnold Hutschnecker, 102, Therapist to Nixon,” New York Times, 3 January 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/03/us/arnold-hutschnecker-102-therapist-to-nixon.html. ↑

5 Jenny Proudfoot, “These Donald Trump Quotes Might Explain Why Someone Destroyed His Hollywood Star,” Marie Claire, 2 April 2020, https://www.marieclaire.co.uk/entertainment/people/donald-trump-quotes-57213. ↑

6 John A. Farrell, Richard Nixon: The Life, New York: Penguin Random House, 2018. ↑

7 “Checkers speech,” Wikipedia, last edited 15 June 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Checkers_speech.↑

8 https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/donald_trump_751630. ↑

9 Paula Span, “Brad Holland: The Artist Uncovered,” The Washington Post, 6 May 1986, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1986/05/06/brad-holland-the-artist-uncovered/a82b7e58-5a36-4da4-8959-c116c4d0c71c/. ↑