Susan Solomon

A Sleet Interview with Stuart Loughridge

I recently met with Stuart Loughridge, a local Twin Cities painter. Stuart's representational landscape paintings are some of the most beautiful work around in our present time. We met one night in his downtown St. Paul studio, where we talked about art, inspiration, technique, and the beauty of public transportation.

In the interview, Stuart references Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet, and it so genuinely applies to this painter as well.

SLEET: Were you always an artist? Did you always know you were an artist?

STUART LOUGHRIDGE: I would say I knew I was an artist as much as any kid who liked to draw would know they’re an artist; I just kept drawing. My high school teachers were very supportive, so I had a lot of extracurricular work with art classes. I drew pictures with my father, who is an artist. I sat on his lap and drew with him and never stopped. He would take me out of school, and we would go out landscape drawing.

SLEET: What kind of artist was he?

SL: He is still a very successful landscape artist.

SLEET: Does he live here in St. Paul?

SL: Denver. I grew up in Denver.

SLEET: I’ve looked at your work, and you’ve been everywhere. What are the landscapes that you like the best? What do you like to look at and paint?

SL: I would say the landscape painter I’ve always imagined myself being more in sync with the landscape here and the landscape further east, in New England. That land tends to tug at my heartstrings more than the big mountains.

SLEET: Do you mean the Atlantic Ocean?

SL: No, more of say, the Hudson River School type of landscape, the more pastoral. I like the Minnesota rolling hills – the trees, the green, the big leaves. It’s more of an England pastoral, rather than the rugged west.

SLEET: Do you have a favorite season that you like to paint? Do you paint all year?

SL: I like them all. I suppose I just like early summer when it is cool and relaxed; that’s the best. And fall is always nice – chilly – I like chilly. But I like winter too.

SLEET: This sounds like a silly question, but do you paint outside here in the winter?

SL: Less. Very little. I tend to do drawings in pencil and occasionally a little oil painting in the winter. Since I work in watercolor outdoors, mainly I tend to work in above-freezing temps. But I have worked in below freezing temps with watercolor. You add a few drops of alcohol to your water, and it keeps it from freezing for a few seconds. When you mix it thin, you can paint it out and it will form these ice crystals, but you can keep painting on top of the ice crystals and then you bring it into your warm car or wherever you are and then it will thaw, and the ice crystals remain.

SLEET: You can paint on Sleet?!

SL: You can paint on Sleet; you can paint with Sleet!

SLEET: I love that so much.

SLEET: The Question I’m dying to ask you: You go out there to the big beautiful world with your eyes and your hands and your paints – and how do you decide your composition, when you’re looking at this whole beautiful universe to pick from.

SL: Yeah, good question. You can break that down into a landscape question, a city question. The main factors that start coming into play – if you step out into the world and are ready to paint, occasionally you are lucky enough where the scene just smacks you. And you think okay, that’s good enough, let’s start. Other times you have to start walking and moving and looking, and the more you walk, the more impatient you get to find your spot because you can find yourself walking for hours. So you have to just settle and pick something and then make something of it. So I usually don’t have exactly in mind what I’m going to paint, I just have to find what’s going to trigger me. It could be anything; I never know what it’s going to be. So I think it’s just about keeping the eye open and fresh. And then a lot of what an artist does, I think, is practice building their aesthetic sense. And I don’t mean that mystically or magically; it’s very much an exercise to develop an aesthetic sense of what your tastes are and the idea of getting into the eye where you are seeing the landscape, rather than just walking through it.

SLEET: So do you decide on the spot then what the “star” of the painting will be, the focus, if it’s going to be about light…

SL: There’s something that tends to hit me, but often with the pastoral landscapes, sometimes it’s just a gentle rolling hill and there’s nothing very smacking about it, nothing terribly intriguing about it, it’s just this real abstract relationship of a hill to a sky. And those paintings are not the ones I develop in the studio per se, but they are worth investigating for me.

SLEET: What gets developed in the studio; I do wonder about that – if you don’t do the whole thing on the spot?

SL: Most of my work is developed as notes on location and those notes are not really for sale, they’re not finished works. They’re very raw, and I’m comfortable making them raw, knowing they’re not for sale. I come to the studio and what gets developed is what tumbles my way through this pile and pile of notes – something like a certain angle might catch me or a certain light effect I see in the painting that I didn’t see before. Often when I finish the sketch on location I’m disappointed, probably 85%, 75% of the time I’m disappointed with the sketch I do. But I know through my experience that that’ll fade and the sketch will start having a life of its own in the studio when I can look at it for a while and ponder it and think, “oh, something in there could really work.”

SLEET: So then does it become something different, when you are alone with it, inside the studio.

SL: It becomes its own nature. I’m not comparing it to nature. Why I’m always disappointed is because I’m always comparing it to what I’m looking at and I’m always falling so short of that mark, but then you get into the studio and it develops its own mark. So then it’s trying to say, “if I develop this into an oil painting or another watercolor, how could I bring out what I’m seeing in there, in what I have on the wall in my studio.”

SLEET: So you’re more of an abstract painter than I thought because you’re working from the thing itself.

SL: I’m very much not attached to getting the exact effect I saw in nature. I love finding my own effect.

SLEET: I looked at your work, and you do some portraits but not that many; is that right?

SL: I have very little patience with working with people and painting. I would always imagine myself to be a figurative painter, and then probably in my mid 20s I realized landscape is much easier on my personality.

SLEET: Is it because it doesn’t talk back, or do you just like it better?

SL: It’s because I can just hang out by myself. I can talk to myself. And I can have a very good conversation with myself.

SLEET: Let me ask you about this: artists and portraits, artists and people: People have a mystical idea that the artist is pulling something out of the model, that the artist is seeing and capturing almost something almost secret about the person, and I never really believed that. I think of Jeffrey Dahmer when he was young – handsome, blonde, blue eyes, nice looking man – if he was sitting on the model stand and anyone could paint him – would the painting differ, if the artist knew or didn’t know? And if it differed, wouldn’t it be totally what the artist was projecting?

SL: Yeah. I don’t think there’s magic in a portrait painting, I don’t. I think there’s magic in a philosophy, and an artist can bring a philosophy to the work and symbols to the work, and that is a highly cultivated practice. The more talent you have as an artist to get the effect of the face, then in turn, the more personality that will come out in the drawing. Every artist is different, though. Some artists can look at somebody and paint a portrait of that person that looks nothing like them, but yet there’s a character that’s coming out in the painting. And there again, it’s getting back to what the nature of the work is. The work develops its own nature. And that, I think, is a striking element or trait, to an artist – if they have the ability to develop their own nature in the work, or does the work just tumble without nature.

SLEET: So you don’t work from photos, then?

SL: Oh, I’ll use photos. I use my watercolors primarily. I’ve been using my watercolors so much in the past years that if I do use a photo – I don’t use a photo for landscape – but if I use a photo for figurative references it is to me almost just like one more piece of reference. I have to have been there; I can’t just paint a photo if I wasn’t there. But if I was there and I have the photo of a person sitting in a certain position and I don’t have a sketch, I just tape it up on the wall and I can start painting my painting. I’m not copying the photo per se. It’s useful but I pretty quickly get off onto my own path before I know it, I don’t even realize it, but I’m not even looking at the photo anymore. I’m just trying to develop what is happening in the painting.

SLEET: Do you always paint from the outside world? Do you paint your dreams?

SL: Occasionally I’ll paint what’s running through my head, but it’s not something I’ve cultivated. For me, it would take a lot of practice to get what’s in my head out and to attach it to what the meaning of it is. Some artists are amazing at that. Most representational artists tend not to be that good at that, but there are ones in the past that have been wonderful at it.

SLEET: You said something about meaning, and I did want to ask you about that. Sometimes I just wonder: Why do we do this thing called art, and I’m betting you probably never ran up against that?

SL: Oh, I ask myself why I do art. I have a lot of different answers for it: I don’t know if I have one answer for it. I ask myself why I do art. I ask myself why do we do art generally. I can answer myself much easier than I can answer the bigger picture. People have so many different motives, and art can be a big money maker, so money can be a motive. For me, I’m not fascinated by money, but I’m fascinated by art and I’m fascinated by beauty, I’m fascinated by mental capacities to create beautiful things and to live a life that revolves around that and develops that, and it becomes in turn some kind of philosophy to live by when you are pursuing art. You’re not pursuing a fancy car, you’re not pursuing material things, you’re pursuing things of the mind and these things to me are one of the few things in life worth pursuing.

SLEET: I’ve noticed that, it’s the way you move through the world; it’s all one thing.

SL: Yes, and how you develop your aesthetics and what you look at, and how you move through the world, what you pay attention to and what you want to pull out . Art is one of the few things that doesn’t precede individuality. Of course, everybody’s individual character comes out but the more this world carries on with technological aspects, the less an individual becomes a player in it. There is invention I suppose, but art is one of those things that needs the individual to be the individual, and I love that because I can be here in my studio, which is my little temple, and cultivate my individuality and my technique and my talent and practices and everything. So it’s something worth pursuing, and when you start pursuing it year after year after year, well you know, what else are you going to do? I don’t have much of a resume for anybody!

SLEET: Would you paint if there was no one to see the work?

SL: I’ve wondered that. If I were really rich and I didn’t have to sell my paintings to make a living, then would I bother showing them? I think I would. But if I had a lot of money, would I still paint? It’s always hard to say. Often people with a lot of money don’t find themselves being artists. Maybe that’s wild to say, but people with the money tend to buy the art. But of course I would still paint. I have stacks and stacks and stacks and stacks of artwork that I paint that I never show, that I sit down at night and look through for my own pleasure. Yes, I would keep working cause it’s built into me to work.

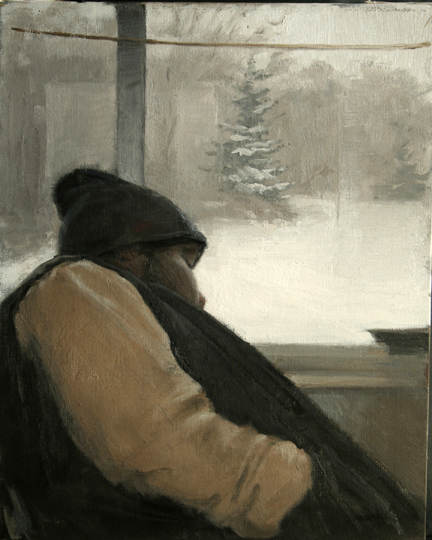

SLEET: The painting I love so much on your site, it’s the sleeping mountain of a man. It’s an unusual picture, and kind of an unusual for you? (ed note: the painting is of a man sleeping on a bus, a large man leaning against the bus window, with a snow-scape behind him, through the windows.)

SL: I love it because it is very distilled, there’s imagination in it. The fellow was actually there and I snuck a photo of him on my cell phone, and as much as I think that a camera is an invasive species in certain cases, I did sneak a photo of him. He was sleeping. And so I plopped him onto my canvas and developed a whole background that worked out better than what I had. And so the whole snowy scene and the trees is my idea. So it’s my landscape painter coming out in the background with the reality of where I was, which was riding the bus to get a cup of coffee, and there was this fellow sleeping. And I’ve always, always been attracted to compositions that deal with public transportation. The work of Harvey Dinnerstein I think is fascinating. He lives in Brooklyn and he still is working today, painting people on the subways. I find that work fascinating, and I always want to develop bus compositions. So for me to have tackled a little bus composition was exciting, and I painted it over a summerscape, so there is green coming through in the clothing of the person, and in the actual painting you can see green coming through. All these little elements I just find fascinating because you can look at the painting and it’s a beautiful paint surface, but you stand back and I think it’s a wonderful composition, and it’s not psychologically intrusive because the fellow is sleeping. I just thought it was a nice way to get that sense of being a rider on a bus and looking over at somebody and you don’t have to bother catching their eyes.

SLEET: It’s a great painting. Do you paint many cityscapes?

SL: I used to, but I’ve fallen out of the cityscape because I think if I were to be focusing on the city, I would be painting more people. But I’m so focused on my landscapes that I just wish I were living out in the country. So I get into the city compositions when I’m riding a bus or transporting myself on my bike, then I’ll get into cityscapes, but it has to have people in it. I’ve kind of lost interest in just the light on the side of a building-type cityscape; there needs to be more to for me to hold my interest. So when I travel, I very much get into cityscapes because it is fresh and it’s new. Recently I was in London doing cityscapes and that was easy. I could capture people, put them in front of the architecture and that was exciting. I would like to bring that element to the work I do in St. Paul, but when I get into St. Paul I get into my heavy, heavy work mode and I need to meet the demands and meet my deadlines, and so St. Paul is a place of work in the studio. So when I travel I can do cityscapes.

SLEET: I see Turner in your studio. Name for me 5 or 10 artists you love.

SL: Yes, favorite artists for all sorts of different reasons. Turner for his grand imagination, but I work in his methodology. His methodology inspires mine; also my father’s methodology inspires mine. And my methodology being working very small watercolors on location so I can travel very light, I can have a very small backpack when I’m traveling; I don’t have to have oil paints and turpentine and all this junk. So I travel very light with watercolors and then develop watercolors into oils or etchings or more watercolors. Turner was a master at that. Constable: fantastic. And then since we’re in England, I might as well bring up Blake, who was probably one of the greatest artists to have ever lived, up there with Michelangelo and Raphael. I also love George Inness, the landscape painter, for Americans. Again, just very symbolic, moody landscapes, beautiful work. That’s kind of the height of the landscape to me. And, you know for portrait work, there are just so many. I think Degas is wonderful, Delacroix is wonderful. Fechin is a wonderful portrait artist, Repin, a great Russian artist; I could just go on and on and on.

SLEET: If you could be in any painting, which would it be? I would be the girl tending bar in Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergere.

SL: Interesting question. I’d pick Christmas Eve by George Inness.

SLEET: Is it because it’s just such a beautiful setting?

SL: It’s a beautiful setting, it’s winter, it’s cold, there’s no house in sight. The man is walking alone. It’s a beautiful melancholy. It’s not the summer pastoral. It’s just a very rugged, rough melancholy personality. That’s where I tend to flourish, when it’s edgy, when it’s cold, when you have to hurry home; that makes me slow down.

SLEET: Do you ever get stuck and have to look at other painters for answers, for an example of how they did something?

SL: Yes, and I’m more and more careful about that, but yes I do look at a lot of other painters, and if I were to be accused of stealing from people, maybe not successfully, but if I were to be accused of stealing from people, it would probably be some elements of Turner, Inness, the more Barbizon style of landscape, and then Degas I probably would steal from them the most heavily.

SLEET: You went to school at the Atelier in Minneapolis?

SL: Yes, formerly the Atelier Lack. I was with the teachers Cyd Wicker and Dale Redpath, lovely people, lovely teachers. I did 3 years; I did not finish my studies. I got impatient, I always get impatient. And then I left and opened up my own studio and got a very, very part time job working at a jazz bar and just dove into my work, and I don’t regret one day of it, it was wonderful. Being at the Atelier was a wonderful foundation for academic. It was where I needed to be at the time. I think the real growing happens outside of school, but I was so happy to have anchored myself down in pure academic, unimaginative work.

SLEET: Did you already know what you were doing when you went there?

SL: No, the only thing I wanted to do when I got there was master what they were trying to get me to do. But as for real paintings, I knew I wasn’t on that road yet and I was awaiting to get there. So when I left the Atelier and got into the studio work, which is no teacher, the clock is ticking and you’re there sitting, the first painting I did was a little 2 x 3 inch flower painting and from there you just have to work up.

SLEET: Do you show your work to anyone? Do you have an “editor”? Do you ask anyone for critiques?

SL: Yes, most often people who are non-artists.

SLEET: Interesting… why?

SL: I don’t hang out with a lot of artists, honestly. Say I’m having my father critique something. It’s very handy; he critiques it on a very artistic level. When people who are not artists critique it, it tends to be a critique as to how the general public might critique the work. I remember reading how Winslow Homer did that. When he wanted to have people critique his work he would have, say, his brother in or his sister-in-law because they weren’t painters, and he wanted people who didn’t paint to look at his work, and with all due respect to other artists’ critiques.

SLEET: Do you ever get attached to any of your paintings, or do you just paint them and then they’re gone? I remember once I heard Ann Patchett the novelist talking about her books and she said, “I’m like a turtle who lays her eggs in the sand, and then I crawl away.”

SL: That’s a good way to put it. I get very attached to certain paintings. And as I like to say, I wish I could afford them because there would be certain paintings that I would love to wake up to every morning that I miss very much. I have one order from a fellow who said “I want you to paint me a painting that you will miss very much; so that could be whatever it is, but whatever painting it is, however big it is, however small it is, I just want you to miss it when you send it to me.” That was a wonderful order. Maybe a few times a year I’ll paint a painting like that, that I really miss.

SLEET: So what did you do for that order?

SL: I’m still working on it; it’s only been a year.

SLEET: Is it big?

SL: No, I’m thinking it could be this painting I just finished of a man sitting on a bench because I will miss this painting when it’s gone.

SLEET: Let’s talk more about methodologies, elaborate on that.

SL: I also work in the print medium, etching, intaglio, which is line work, on copper. I work in oil of course, and I work in a big format 3 x 4 foot generally, and then I work in watercolor. And it’s interesting, I think, to talk about the way I have over the past few years – it’s kind of turning a big ship when you operate a studio and you start getting clients collecting your work, to change how the format, or what they’re buying, is like steering a big ship. So before, people were buying the work I finished right on location. You call that plein air or alla prima today in modern terms. But as my method developed, I realized I didn’t want to sell my watercolors. There was one time I got back from a month-long trip in Italy and I had developed about 30 or 40 watercolors, and when I got back I ordered 30 frames, (I make my own frames), and I realized the last thing I want to do is put all these watercolors up for sale and sell them and have them be gone because they are material. So that was a turning point for me to say “I’m going to hold onto these watercolors from here on out and I won’t sell them.” So as there was a dip in sales because of that, there had to be a spike in work, and the spike in work was developing paintings off of the watercolors and developing material off of the watercolors. So in turn, what that has turned into is a client can come by the studio, look through this stack of watercolors I have, all of which most of them I absolutely adore, and then they can pick out their favorite one and then they can tell me their price point, and I can paint the watercolor, re-create it into an oil or a watercolor according to their price point. So that way, I’m not turning down sales.

So by holding on to my studies, I freed myself to fit the client's price point, but I control the content. So also what that means is I’m usually booked out for orders, and so right now I’m booked out for probably 4 or 5 months with work that needs to be painted.

SLEET: So you don’t need galleries.

SL: I’m more and more focused on trying not to need them, but I still use galleries for show space, and it’s nice to attach myself to galleries that I just like the relaxed feel of it. I’m very much of the mind to just do it on my own for now and kind of go my own way about it. But it means that if I’m out of town, often sales won’t happen. So when I do come back into town from the travels, it is really 10 to 12 hour work days, 6 days a week. I become the workaholic. But when I travel for a week or a month or a few months, then I can become the painter out in the field and relax and work for a few hours a day, but I’m still working, still observing, I’m still walking around trying to find the spot to paint.

SLEET: What about the State Fair?

SL: Oh, the State Fair is wonderful for the arts here – it’s fantastic. I was not accepted this year.

SLEET: They didn’t accept you??

SL: It’s my 3rd year in a row of not being accepted, but at the same time it all balances out I suppose, because the first year that I was accepted I got the blue ribbon on an etching, so I was able to sell that etching 25 times, most of those with handcrafted frames. I love the State Fair and I think they’re fantastic, and even if I don’t get in I think it’s a wonderful little talk of the town type thing. SLEET Is it sad to be rejected; how did that feel?

SL: Oh it feels fine, to hold any expectations on a jury is just asking to let yourself be let down.

SLEET: I love that you said that!

SL: So I enter it in knowing that it’s going to be rejected, and so when it’s rejected then I’m not disappointed. But you really have to exercise the non-expectation idea - and it’s people. To have expectations on people is one of the most absurd things. I have expectations on people that they be kind and civil, and even that is hard to have fulfilled. So when it comes to a jury, oh man, whatever!

SLEET: It’s so whimsical.

SL: It’s so whimsical, and then it becomes the talk of the town – who got rejected and who got in. It’s hilarious; I love talking about it. And I have no shame in saying I got rejected, no shame, absolutely none, because it’s not the determining factor. I’m making a living on my work. The work that they have rejected in the past – they rejected an etching one year and it’s my best selling print to date; it hasn’t at all deterred sales. They rejected a painting last year and shortly after, the painting sold. I always applaud the State Fair and for all the work they do.

SLEET: I love the State Fair. I moved here from Philly a long time ago and one of the first things I did was go to the Minnesota State Fair. I had never seen so many people lined up so orderly to get cookies or to see the butter girl in the freezer being sculpted.

SL: And trying to cover so many bases. Granted it is some of the same old distracted mentality of the American empire, but it is still fascinating to see people getting there early in the morning to watch the animals wake up and then walking over to the Fine Arts Building and then going to get their breakfast and then doing this and then doing that. It’s kind of a culmination of what’s good about Minnesota and not good about Minnesota! And I think the state fair would be all of that in any city. I know people go into the State Fair documenting it and I’m sure there are people who have gone into the State Fair thinking, okay I want to work the State Fair this year and to work it. I always think it would be fascinating to just live with the State Fair for a few years and just paint the people and paint the gossip; I think that would be interesting too.

SLEET: Well just riding the bus to go to the State Fair is so great. You see the workers going in.

SL: That’s fantastic. That’s great subject material there. I like riding the 54 bus to the airport early in the morning because if you catch the bus right, you catch a shift and you see the workers get on and get ready to go. I think all that is fascinating; it’s great material. I love taking the bus. I always think ahead when it’s happening and I plan out and I bring my bus sketchbook, and I sit on certain seats depending on what views I want and then whatever happens happens. The interactions can be absolutely bizarre.

SLEET: Do you ever ride the bus just for art?

SL: Yeah, sometimes I’ll just walk down University Avenue and walk and then if I’m passing a bus stop and I see the bus, I’ll get on the bus and ride that for a while and come back and you can definitely make a good few-hour afternoon out of that. And sunset time, I love crossing the river on the bus. And yes, the bus is a wonderful source and public transportation I think is fantastic, and the more private transportation we have the worse it is, I think. The concrete ribbons are just taking over, and it’s too bad. Death to cars.

SLEET: Death to cars.

We toast.

SLEET: So to wrap this up, generally, let me just ask you: What is your goal with your work?

SL: Goal? To make beautiful artwork. Simple as that. To make something that is wanted for aesthetic reasons, rather than exterior reasons (political, social context, etc, although I have side goals in line with such themes). A sample of one of my personal goals is to succeed in using excellent line-work expressing content to match it. Or excellent composition and color harmony to express a landscape. To apply Formula to Feeling and understand better the ancient ways of doing so. Otherwise, on a more philosophical tone, to survive and not become bitter. Keep painting. Build a body of work – which takes a lifetime and a dedication to a lifestyle – and “suffer not the fashionable fools who boast of expensive advertising for contemptible works of art.” (William Blake, intro to Milton). Art comes at the expense of much, and my sacrificial altar is always in use….

SLEET: Tell me about making something beautiful.

SL: Beauty is a big topic. Partly to cultivate my own sense of aesthetics, and cultivate in complete disregard for what is being done today, as if closing the door on the chatty art arena. Rilke said it well in his “Letters to a Young Poet,” the first letter in the book.

Beauty is also that which inspires me to paint, but again, I must be attentive, away from the chartered streets, to notice it. It takes practice and much silence. It is something to live by and for.

To see more artwork, please visit his site at www.stuartloughridge.com. And for anyone living in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area, Stuart has etchings hanging in a casual, ongoing show at the Dunn Brothers Café on West 7th Street between Walnut and Chestnut, downtown Saint Paul.