Sophfronia Scott

The Night Viera Kissed Her

My name is Marie Gloriana Fisher but every day, before dawn, I become the great Spanish artist Vidal Viera. What would my grandmother say about this? When she died she left me the money to go to Paris so that I could paint and, the note in her will had said, “Find that missing part of you.” My grandmother liked that I was painting, even if she understood none of what I created. I think it tickled her to have something going on in the farmhouse that wasn’t about baking crusty bread, getting stubborn chickens to lay or sewing new curtains to go over the kitchen sink. She was the one who, on the day I was born, insisted I have the middle name Gloriana. “You can’t expect her to walk around with a name like Marie Fisher and do something glorious.”

“Who says she has to do anything glorious?” my mother, full of the fretfulness of one who has just given birth, had replied. “If she stays out of trouble I’ll be happy.”

Even now, I can hear how my grandmother must have sighed and thought this was why she would not have chosen this woman as her son’s wife.

My grandmother wanted me to be glorious. Instead I have become someone else entirely. I know this because if I were truly myself I would still be sleeping at 4am. I know this because when I rise I am not groggy or tired or complaining. I wake with a consciousness that is clear and purposeful—and humble. I know exactly what I’m supposed to do.

I draw. Within ten minutes of rising I have made tea, and I am at my table working. I have never done this before yet for weeks running this has been my habit, one that has failed me before in all the years I was learning to paint. And now, because I am Vidal Viera, I have never been more productive, the canvases blooming with color under my hands are now alive and Viera’s apprentices are withering with envy. They want to know how a girl, not even twenty-five years old, and from Illinois no less—could come to Paris and have Viera-like genius sprouting from her brush in only a few months while they, the tempura-stained wretches, had waited for years for the chance to work with Viera; had slept on the steps of his studio and labored under his dark eyes and contemptuous comments. How does she do it?, they wonder.

At Viera’s studio, where I go every afternoon to paint, he has installed me in a well-lit, attic-like space above where the apprentices work. I must climb a tight spiral stair to reach it. He watches me closely but he doesn’t get too close. I am not his lover—even he recognized how absurd that would be. He is not a narcissist, whatever people say about him. But he likes having me nearby.

The noises the apprentices hear above their heads are the sound of Viera and myself walking around and around my easel, addressing each other and addressing the painting. He wants to know what of him is in the colors. How much of it is me? When I have told Viera the story of my full name he says, “From now on you are Maria Gloriana! That is an artist’s name! Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.”

“Why?”

“Why? Why should you be anything other than what your very smart grandmother already christened you?”

I admit becoming Maria Gloriana was no great leap and for some reason it made my slipping into Vidal Viera that much easier, like the road was shorter and paved smoother somehow.

Viera pours even more of himself into me. He thinks I am a better chance at immortality—better than his paintings, better than his loves, better than his children. I do not protest. Would a river complain when it rains? He teaches me about philosophy and art and the way people look at paintings. He makes me understand why my grandmother had liked my abstract work better. Before she died I had begun to focus more on the abstract and she, for reasons I did not understand, enjoyed those paintings more. She had even said she recognized it, could tell what I was feeling by the shades of blues and circles that floated together to form a woman’s body. It didn’t make sense when she used to argue with me over the way I had drawn a simple corn stalk. People will always argue with you about how a tree looks, Viera says, because everyone has their own idea what a tree looks like. But paint a scene with no such grounding image, where they are forced to react to the color, light and movement—then you will grasp their attention. You are always painting for your peers, but you must also paint for the common man. Or my grandmother, I think. I must paint for Viera and my grandmother at the same time, all the time.

He doesn’t say so directly, but because I am him I can look through his 62-year old eyes and know Viera fears death. “The students, they will all leave me eventually,” he said one day. “They don’t care about me, they only care about the painting. What will be left of me when I am gone? These paintings? Yes, there will be canvases everywhere, in museums all over the world. But what about my voice? What about my thoughts? What will become of those? Who will remember those? I fear the shadow days and they are coming for all of us. But you will hold all this for me.”

What will I hold for myself? I wonder. What have I become?

When I first arrived in Paris I was still smarting from the snide comments of my mother who had said I was wasting my grandmother’s inheritance by paying for a ticket to Paris, so I didn’t have the nerve to inquire about an apprenticeship at Viera’s studio. He rarely worked with female students and I couldn’t face an outright rejection so soon. Instead I waited outside Viera’s studio and when the day’s work was done and the wide wooden door opened and the apprentices rumbled out into the street lighting cigarettes and shaking their heads in frustration I followed. It was Paris 1950, just as people were finally letting go of the German gloom they had carried in their step all those years. The city could be vibrant again.

The apprentice I chose hung back just enough so I was able to address him apart from the others. He had a luminous long thin face, like he’d stepped out of an El Greco painting, curly black hair and sad black eyes. I touched the elbow of his jacket, my fingers finding the fringe of fraying threads where its fabric was coming apart. “Parlez-vous anglais?” I could work with a French, or even a Spanish speaker if I had to, but I was hoping for one less obstacle in this quest at least.

He kept walking, but nodded as though he heard that question frequently. “I am a painter,” I told him as I fell into step with him. “I want to learn Viera.”

“He has no female apprentices.”

“I know, I know. But you are one of his apprentices. I can learn from you. I can pay you.”

He stopped then, tossing a few words to his friends saying he would meet them later. He looked me up and down, from the black beret I wore with my brown curls crushed beneath it, to my shapeless black coat, slacks and simple black flats. I had dressed carefully that day, knowing this might happen and wanting to ambush any thought of temptation before it began. I think it worked because I could see a kind of disappointment wash across his face and then the consideration of his wallet coming into play. He shrugged. “All right, I am Giancarlo Gilot.”

I offered him my hand and shook his. “My name is Marie. Marie Fisher.” He winced at the sound of my name.

“I may teach you,” Giancarlo said, “but I want to see your work first. Where do you paint?”

“Please, don’t just teach me. Teach me what Viera teaches you.”

“I might, if you’re worthy. Your work?”

“Come, I’ll show you.”

I gave him money for the Metro and we rode in silence but in my mind I was conversing with him in all my nervous verbosity. I told him of the long trip across the Atlantic, how I was sure I’d never find a flat and I wondered if I was being taken just a bit on the rent, but I couldn’t resist the room because, though tiny and shabby, there was space enough to paint and glorious light and I was just wanting to fall on my knees everyday because I was so happy to be in Paris; that my life was finally beginning and I would finally learn what it is to live and put a stopper in the part of me that has spilled out yearning since the day I turned 14. But none of those things made me sound like a serious artist so I remained silent. Artists could not be so happy—the look of the apprentices leaving Viera’s studio told me that.

When Giancarlo walked into my flat he looked around, appraisingly, as if he recognized it, had been in so many rooms like it before. There was the long and narrow single bed, in a corner and pushed against the wall. There was the tiny kitchenette area, with a hotplate and a sink that served more for cleaning brushes than the preparation of food. There were the canvasses, the easel, the work table, the papers and brushes—some organized and some strewn across the table where I had left off the day’s work.

Giancarlo started with the painting on my easel. As he perused it I pulled out other work that leaned against the walls and were stacked one on top of another so he could also see the corn stalks I had painted at home.

“All right,” he had said, nodding. “We can begin. Tomorrow, if you like.”

At first the work had not gone well. Day after day, canvas after canvas, Giancarlo could only speak to me in terms of what was missing: no style, no color, no technique, no sense of proportion. The frustration tasted metallic on my tongue. I knew my work could progress but I felt like I was in a glass box pounding on the walls. I could see where I wanted to go, but I couldn’t get there.

Giancarlo and I would sit on stools in front of the easel and he would take long drags on his cigarette, and blow thin streams of smoke into the air. One day he said, “Your brush stroke is too timid. There is no strength to it.”

I responded by throwing my brush across the room. It hit the wall leaving a smattering of blue spots near the window. “How’s that? Is that a stroke strong enough for you?”

Giancarlo laughed. “Good, now you know what the apprentices all feel when we leave his studio at the end of the day.”

“Why? Is Viera so difficult?”

“He is the worst kind of great artist. He is the genius whose genius is so inside of him he can’t tell the world how he does it. It’s beyond him. I think he gets just as frustrated with us because we don’t always understand him. You would almost have to become Viera to please him. But who would want to be him? He’s a miserable wretch. Give me his talent. You can have the rest.”

Become Viera? My fingers tingled at the tips and I wished I still held the brush I’d thrown in my hand. Was that possible—to take up someone else’s thoughts and feelings—their very being? I didn’t understand it and yet this was the first thing Giancarlo had said that made sense to me.

“Tell me about Viera,” I began slowly because I didn’t quite know what to ask. “What is he like?”

Giancarlo laughed. “He is a spoiled farm boy. A peasant. How he became such a great master I don’t know.”

I breathed in and saw a chance. Wasn’t that what I was—a spoiled farm girl? Back home I had looked on every animal and their various sacrifices with disdain. But there was more—something more…there had been my utter dissatisfaction with the mundane. I had seen the beauty of the farm, yes. That’s why I sat in the fields and tried to paint them, the way the color of corn stalks change as they grow and the burning hues at sunset when the fields turned red.

When I wasn’t painting I was grumbling and complaining. “I’ll never get really good! If I could go to Paris, I could learn so much. If I could only go to Paris…”

My grandmother would listen to me and smile as she sat cutting up her old aprons for me to use as rags.

The world of southwestern Illinois seemed small, so small. Attending the local college had been enough to start me on the journey but after graduation as I sat at home and flipped through art books the images on the page told me there was more, so much more. Each time I closed one of these books I would be short with my family, even downright rude. A single painting could transport me thousands of miles away only to have me go downstairs and find everything discouragingly the same. There in the kitchen my mother, who never bothered to dress properly since my father’s death three years earlier, wore the same ugly green housedress. She would peel potatoes to mash in the same way while the parts of a recently dead chicken lay next to the sink awaiting their too common destiny in the frying pan. My grandmother would assist her, taking the discarded brown curls of potato skin and sweeping them into the garbage. I would join them at the cold metal table, my nose wrinkled. “Chicken again?”

“Little Miss Peevish” my mother would say. I always ignored her. My grandmother would smile.

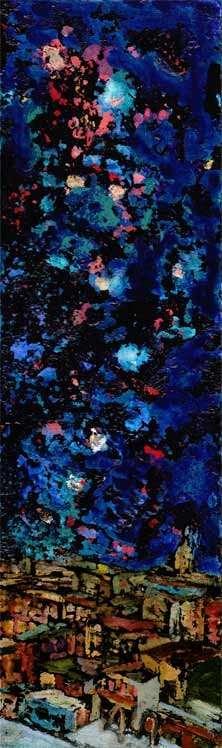

When I was peevish my grandmother would slip money into my pocket and I would take the bus to Chicago and visit the Art Institute, a trip that made me feel in equal parts better and worse. That’s where I had first seen the Viera, on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “Seduction of the Cosmos” was a fantastic mural-size black canvas that Viera had assaulted with a riot of color all inspired by Celeste—the muse and lover Viera called his “living night sky.” The painting depicted his ongoing struggle to bring heat and hope to the cool and inviting darkness he once said caused him to dwell within her being. The canvas felt full of secrets I longed for it to reveal to me. I would sit in front of it for hours.

One day I returned from just such a trip to learn my grandmother had died. My mother says she went upstairs for a nap and never woke up.

If indeed Viera was a spoiled farmboy he must have felt, perhaps even still wrestled with, the same peevishness I endured. He must have the same grasping for life. During our sessions I began to mine Giancarlo for specifics on Viera. Whenever he tried to show me a particular brushstroke or discuss a particular concept I would ask, “What did Viera say about it? What did he say exactly?” But he could never remember precise wording and soon I felt like I was ravenous for Viera but couldn’t sustain myself on the crumbs Giancarlo doled out. I begged Giancarlo to loan me books Viera had written. Such things I learned! I devoured the books, but still something was missing. I needed to hear his voice, to feel the weight of him as he moved about a room, to see his hands.

One day Giancarlo arrived at my studio and said, “Come. We are not painting today. Viera is giving a lecture for a group of American students at the museum. We will go.”

We arrived a full thirty minutes early but every seat and nearly every bit of floor held an occupying body. Still we managed to shoehorn ourselves into a space on the left side of the room. At the center of the small stage sat an easel with a large blank canvas. To the right of it was a chaise upholstered in light blue fabric.

“Ah,” said Giancarlo, nodding. “This is why so many are here. He will paint for his lecture. It is his way sometimes.”

The crowd hushed and Vidal Viera strode across the stage. He held a brush in his hand and wore a green canvas apron splattered with paint. He looked as though he had simply left his studio and walked across the street into this one.

“Good afternoon,” he said, acknowledging his audience with a nod and a slight bow. “Whom would you like to meet today, eh? Or shall I transport you somewhere to a place, perhaps a scene that you thought you knew? Let’s see what the canvas says today, shall we?” The audience applauded while Viera filled his brush with paint. When he spoke he seemed to address the canvas and the audience at the same time.

“In the first hour or so of the work, it is difficult to tell what will come through. Is the image real or a fantasy? Dream or a memory? Ah! Look at these lines—thick, black, curvy. I see in them the lovely dark curls of my beloved Celeste, my living night sky, she whose moon and stars light my darkness. Is it her? Midnight blue? Yes…the dress she wore to dinner the other night. Or is it the dark sky itself? What is she contemplating on this night of the cosmos?”

In this moment the brushstrokes weren’t as important as the creaking sounds the boards of the stage made as he stepped back and forth across the wood. His wiry gray hair was cropped close to his scalp and his dark brown eyes radiated a brilliance that cut straight through the room. Sometimes he peered closely at the paint he’d placed on the canvas. Sometimes he stood back or stalked all around the easel, all the time speaking as though addressing an adversary—or a potential lover. I tried to ignore what he was telling us and hear only what he was saying to the painting. He was searching, seeking. In any minute, I could feel it, I knew we would disappear and cease to exist for him. I had to pay close attention and wait for this moment. I needed to slip into this vital crease before everyone else disappeared so I could go with him.

I felt movement in the room. There seemed to be a collective intake of breath. I opened my eyes and an “Oh!” escaped my mouth. There was the actual Celeste, walking across the stage barefoot, wearing only an oversized man’s shirt. She didn’t acknowledge the audience. In fact it seemed she had merely entered her own living room. She draped herself across the chaise, one elbow on top of the back as she leaned against it and looked away from Viera. Her dark hair fell heavily down her shoulders and even from the audience I could see the green spark of her eyes, the exact shade I had seen so often splayed onto Viera’s canvases. I could feel the way her hips curved like the sides of a cello to fit perfectly beneath his hands. The inevitability of her melted into me. If Viera were painting, truly painting, of course she would be there.

“Will I bring flowers to Celeste?” he was murmuring. “Of course I will. It is her birthday.” I could smell the lavender as he painted the branches and let them entwine with the woman’s hair. It seemed I was on the stage with Viera, just behind his shoulder, and then, at last, I was in the conversation with him, questioning, listening.

“How old will Celeste be?” I think to myself just as Viera sputters “Pah! What insolence! Never ask a grown woman her age! As if it matters.”

“But what about the lines? Wouldn’t you paint more lines on an older woman?” This time I knew the answer before he responded: “No, because I paint her as immortal.”

“What if the stars aren’t really like that? What if someone says that looks nothing like the night sky?”

“This is the sky as I feel it every evening in her arms. If you want real stars go buy a telescope.”

“Yes.”

I left the museum that day with his voice and his hands in my head and the conversation between us ongoing. Then came the moment in the art shop when I caught myself unwittingly about to purchase, not my usual brushes, but the kind I had seen Viera use during his lecture. I had picked them up without a thought, as though I bought those brushes regularly. In that moment I knew I had slipped into him at last. Once I could do that little bit I wanted more.

I quizzed Giancarlo on the master’s habits. Viera did his real painting in the afternoon when the light was best but he rose before dawn every day to draw. I remember upon hearing this that something within me changed. It was not like a light switch, easily tripped. It felt more like a dial within me and something had taken the dial between its fingers and started to turn it, to turn me. I did not say to myself, “I must do the same, just like Viera.” I did not make schedules, resolutions or promises.

I just know the next morning I woke on my own, at 4am, without effort. I made tea, took my cup to the work table and began to draw. In the afternoon I painted. The whole time I listened to the conversation still ongoing between Viera, the canvas and myself. Within three weeks Giancarlo was staring at my work, dumbfounded, as I paced the tiny space of my studio.

“How are you doing this?” he asked. “It is Viera and yet it is not Viera. It is…you? How can this be?”

But I wasn’t listening. I wanted more. I wanted be in Viera’s studio to soak up the smells, the light, his spirit. I craved his element because now it was my own. “Take me to Viera’s with you,” I told Giancarlo. “There must be a day when he isn’t there, right? I just want to see it, to be there.”

I braced for a fight, but Giancarlo offered none. “Wear what you wore the day I met you,” he said. “You must blend in. Bring this canvas you’re working on. They will notice you if you’re standing around doing nothing. You must paint if you come to the studio.”

My fingers tingled. “Yes, I can do that.” It was so much more than I had hoped for.

Two days later, my wrapped canvas under my arm, I followed Giancarlo into Viera’s building. Immediately my ears filled with the drone of many voices speaking in low tones. Giancarlo motioned for me to follow him up the staircase.

“This is good,” he said. “The dealers are here today waiting to speak with Viera. He’ll be busy with them the whole time. The American ones alone will occupy him for hours.”

We kept climbing stairs until the voices were beneath us. At last Giancarlo opened a door and we entered a spacious room that looked like it took up the whole top of the building. Tall windows climbed the walls. The light was magnificent. Twenty pairs of eyes turned on us as we entered.

“Giancarlo? Who is this?” one tall, blonde apprentice asked.

“Shush,” he replied. Giancarlo led me to a far corner, the least well lit. He brought over a stool while I unwrapped my canvas. “Just stay right here and do your work,” he said. “My place is over there. Do not move until it is time for us to go.” And with that Giancarlo left me.

But then, not even an hour into our work, the master arrived unexpectedly. He whisked into the room muttering “tiresome gadflies” and began appraising the work. “Ha! Still wasting my time I see,” he said to the blonde painter. The rest of the apprentices began to fidget, especially Giancarlo, who had brought an interloper without permission. But when Viera first saw me he came toward me quickly, as if drawn by a magnet. He took one look at my canvas, then at me, and we began our dance of walking about the painting. He seemed to recognize me and I felt this flood of relief—not because he wasn’t angry, no! I felt relieved because in that moment I felt whole, as though some part of me I didn’t even know I’d lost had come back to me. Viera seemed to feel this too and he called the apprentices over to lord over them our completeness.

“You fools! You are so blind. Can’t you see she is me? In fact, she IS me, only MORE! Ah! If only I can be so, but I am Viera and I can go no further—I would split this sack of guts containing me if there were more of me. But she has the space—she can take me in and become more. Oh my soul!

You should all crawl on your knees and beg for the chance to see one moment through her eyes! She is a girl and she has more art in a lock of her hair than you have in all your fat heads put together!”

Of course the apprentices do not understand. One day one of them comes in dressed in a green canvas apron and brown dungarees similar to Viera’s. The master throws him out forever. The student had been ludicrous, of course. It was more than just a matter of dressing like Viera. It’s a matter of taking things in and filtering them through these new layers of webbing that I feel now hang throughout my insides. When I take something in—reading, a view, the shade of a particular watercolor, a person, a smell—it all falls through this webbing and as all of my own insights and thoughts are filtered out it comes out through my eyes, always the eyes, and I see how he would see it all.

Sometimes I look in the mirror and I am shocked to see my eyes are still blue. I expect everyday to see that speck of brown, like a bit of melted chocolate, appearing on my irises and then spreading, day by day, until my eyes are completely buried in the dark earthen color that is his.

One day it is not enough for me to just paint like Viera. Because, spoiled farm girl that I am, I want to know more. I want more. I want him to still that persistent cold yearning I had felt back home, to confirm there was more to life and tell me how to grasp it like we grasp the brushes in our hands. “Please, no more of death,” I tell him. “Teach me about life.”

“It is not time for that lesson,” Viera says. “Besides, it is not something to tell. It is something to live.”

I want to argue with him, but I can say nothing to him that he hasn’t already said to himself many times over. I fear I will stay in this room and be his vessel forever.

Celeste, however, surprises me.

“Give him back to me,” she says one evening, sneaking up behind me as I sit at my easel.

“I don’t have him.”

“Don’t you? You are always with him.”

“No, it just seems that way because I am him. He is rarely here. He is not here now.”

She seems confused by this. She looks around the room. “But I thought I heard, sensed his presence! I always do.”

“I see through his eyes,” I tell her. “I love what he loves. What makes you think I love you any less than he?”

Before the light of realization can dawn, I stand and kiss her, just as he does, with my paint-stained fingers on her face and the faint smell of turpentine on my shirt.

She does not resist.

She smiles shyly, as I’ve seen her smile for him. “You taste of paint,” she says. “Just like him.” She pulls her wrap over her shoulders, letting one side fall to reveal a bare tan shoulder. She walks away from me then.

And I follow.

There is something wondrously life-affirming in the warmth of her skin, in its tan coloring and in the freckles sprinkled like cinnamon all over her back. In our lovemaking, in seeing her this way, I understand why he loves her so much. Is she the secret to life?

“I want to paint you,” I tell her afterwards as we lay, limbs entwined, under the cotton duvet.

“You mean the way he paints me?”

“The way I paint you.”

The next morning she climbs the spiral staircase, rising like a Venus ascending. I have already prepared the blue chaise for her. The apprentices are hushed below us. She reclines. I begin to paint.

In the days of painting Celeste I feel giddy and drunk. We laugh like schoolgirls at play. Now the world sparkles like a brilliant orb and Celeste and I are dancing on the surface. I see her not in the night sky, as Viera painted her, but as a queen springing forth with life-giving waters. I surround her in the blues of the ocean and the conversation I am having with the canvas—and at times with Celeste—is all about movement and flow.

“You must be free to wander about in the painting,” I say. “I will make you ethereal, floating.”

“Free,” Celeste repeated as though hearing the word for the first time. “Free.”

I mix the next color and do not hear her because this Celeste coming forth on the canvas is commanding my attention. I pace the floor.

Viera stays below and says nothing. At times I can sense him there, standing at the staircase, his hand on the rail, but he does not come up. He is listening. I ignore the growing pain he feels because I know only his pain will make me stop painting Celeste.

When the painting is done I am eager to show off to my first teacher. I bring Giancarlo up to see it. “Ah, Maria!” he breathes and clutches my arm. “Be careful. You must be so very careful.”

“What do you mean? Isn’t it good?”

“It is sublime! But Maria, you cannot be too good. Not yet! You must not outshine the master, not while you still work under his favor.”

The part of me that is Maria Gloriana wants to laugh. The part of me that is Vidal Viera understands implicitly. I feel I hold Viera’s heart in my hands. The rest of me is filled with Celeste like she’s an underground spring feeding the life in both of Viera and myself. I nod and tell Giancarlo, “Yes. I will be careful.”

And yet I am not so careful because something is happening to me that makes me not careful. Celeste loves me because I am Viera, but in loving me she has brought me back to myself. Only I don’t know this version of myself. This me is fearless. This me takes Celeste and tells her we must only work together in my studio now. I insist we can do this because I will still paint with Viera and she will still pose for him. No one can begrudge us a few hours together every day.

But I am concerned about what Viera will see in my canvases. I cannot hide that Celeste is no night sky to me. I asked him for life and now I find I don’t have to ask him anymore. The answer is Celeste. Not Celeste herself, but she has become a kind of launch pad, a lever of transcendence. From Celeste I can leap into the air and suddenly, paintbrush in hand, I am flying. When I paint Celeste the colors that come are no longer the result of a pitched battle of frustration from someone trying to impose artistry on her form. Instead my canvases pulse with free flowing light and energy and passion. I feel Viera seeping away and out of me day by day, but why should I care when Celeste looks at me—me—the way that she does? Why should I care when we laugh as much as we do?

Because Celeste and I never work in silence, overthrowing the old image of the artist staring intently at frozen skin. We are flesh and blood women who walk arm-in-arm through the streets of Paris, and when we are in the studio the walk only continues. I have never felt so alive, so truly glorious. I am Maria Gloriana.

We dare to go on in this way. I keep meeting with Viera even as Celeste continues to pose for him. But every day that follows is showing him that his results are not the same. He grows increasingly silent. I wonder if I should keep going back to Viera, but at the same time I know why I keep going back. I am waiting. I am waiting for what finally happens this rainy morning when we have painted in silence a full two hours. Then he stands and throws his canvas to the floor, swearing in Spanish and English.

“This is shit! This is shit!” He turns to me. I grip the brush and stare. “And you? What are you doing over there? Just what do you think you’re doing?”

He comes over to my canvas. “Look at this! Light! Light everywhere! Where does this light come from, eh? It comes because you have stolen my light!”

“Viera,” I say, my voice level and calm. “I have stolen nothing from you. Celeste is still here, Celeste lives here, Celeste still poses for you.”

“Ah! But…not…,” he says, poking a finger into my chest, “the way she poses for you! How can that be, eh? Eh?! How can that be?”

I put my brush down. Viera pulls out a cigarette and lights it as he begins to pace the room.

“I was content to share her,” he says. “I’ve been more accommodating to you than I would be for anyone else! I knew you were sneaking off to God knows where, but I thought it was natural. You are me and, of course, the attraction would be obvious.”

“Yes,” I say slowly. I want to make some preparation to go. To cover my canvas, or pack up my tools, but I know that will only provoke him further. He keeps talking.

“But now I see the real danger—you’ve gone beyond me! I should have known! I didn’t think it was possible—we have been so attached, so of one mind! But it is true what they say—the students leave! They all leave!”

“Viera, whether I stay or not, whether Celeste stays or not,” I stand and touch his arm. “You are still going to die someday.”

His hand comes out so fast. It’s like he would do if he were to whip a paintbrush through the air to create a supernova on canvas. But his hand lands across my right cheekbone, and stars burst into my field of vision as I fall to the floor.

“There it is! Ha! That’s life! There’s your lesson! There’s your answer! How does it feel?”

He is right. I do see what he means. My face hurts and I feel furious, yes, but this is like the other side of the coin, the other side of what I have learned from Celeste. And this is why I have waited for this moment—to confirm I have truly taken from Viera all that I was meant to learn.

Viera goes to the window and continues to smoke, his back to me. We are finished. I pack my things and take my canvas.

However I do not leave the building. Instead I retrace the steps I know will take me back to Celeste’s bedroom. The door is open. “Celeste! I’m leaving! Viera and I are done.”

But Celeste is already packing. My heart falls into my feet but I am hopeful.

“What are you doing? Celeste, where are you going?”

“Away, my love, away. It is time for me to go.”

“Okay! Then let’s go! We’ll go together. This is perfect. I’ll get a bigger place and then we can do anything…”

She is shaking her head. “You have freed me,” she says simply. “Look, Maria, you are leaving. You will leave here and everything will be different for you now. If I go with you, how will that be different for me? I would be exchanging one artist for another.” She smiles. “Even though you are the better artist.”

“But I would let you be different. You could do anything you wanted.”

“Yes, but I don’t know what that is right now. I think I will have a better chance of figuring that out if I’m on my own.”

“What do you think will become of Viera? Have we wounded him? Will he die?”

I hear her snap the suitcases closed. She sits on the bed and looks me directly in the eyes. “Yes, and so will we all. But he will not go, not yet. You of all people know this so well, so well. You will have tethered him to life. He’s probably got enough anger at both of us to fuel him for at least the next decade. As for me? Well, you gave me back my life. And I will forever love you for that.”

Celeste puts her long cool fingers on my face and pulls me towards her. She kisses me on the forehead. “You gave me back my life the night your Viera kissed me. Perhaps I will do the same for you, yes? You are still Illinois farm girl at heart, very much like him. One day you will have a proper husband—one who will let you be the great artist you are.”

I know what she says must be true because I am not crying. Yet I feel pierced—am I bleeding inwardly? I follow her out the door in a daze and say nothing as she gets into the cab and says goodbye.

That night I drink. I am no drinker by nature, but the shots of ice cold vodka goes down smoothly and I even manage to procure a bottle to take home with me. I follow drink upon drink until it finally comes to me—my grandmother’s voice. “Find that missing part of you.” There is only one place I can go.

I pack a small bag with baguettes, chocolate and the vodka. I take up my painting tools, still on the floor where I dropped them earlier. I stumble out the door to find a train that will take me to the country. I have heard that the wheat fields of French countryside are not unlike those of Illinois. If I can find one, and if I can be there when the sun hits the wheat just right, it will be like I am at home.

The sun is up when I leave the train and hail a cab. The driver is reluctant but he stops when I spot my chosen field and leaves when I press money into his hand and wave him to go. I make my way down the road alongside the field and when I come upon a grove of cypress trees and I lay down and fall asleep beneath them, my arms wrapped around my things. When I wake the arc of sun tells me it must be past noon. I look around and see if I go a little further up the road I will climb a small green hillside that would give me a better view of the fields. Once I am perched there I am struck by how much it all looks like home. I almost expect to see my grandmother walking through the wheat, waving at me to come in for dinner.

The heat of the sun feels good. The chocolate melts in my mouth and soothes my soul. The field vibrates with color, the waving grain a new red sea undulating towards me. I can feel the blood pulsating in my fingertips. I lift my brush. In this moment I begin my masterwork. In naked confidence, without question, I know I am now painting as I am meant to paint. The show that comes of what I paint from now, the show that makes me, is called Gloriana: The Glorious Light.

I have my own full studio now. I work. I work, forever on the verge of discontent. I ride a wave of passion, love, and fury every single day. In the afternoons the room is filled with my own apprentices. Every day I enter and pause. I walk up to each apprentice, especially the new ones, and peer steadily in their eyes. We only begin when I have done this, only after I have examined the eyes of every painter. I know how they whisper. They think this is my form of craziness—all artists have one don’t they? I ignore them and I keep looking. I look for the one who would be me.

I have my own full studio now. I work. I work, forever on the verge of discontent. I ride a wave of passion, love, and fury every single day. In the afternoons the room is filled with my own apprentices. Every day I enter and pause. I walk up to each apprentice, especially the new ones, and peer steadily in their eyes. We only begin when I have done this, only after I have examined the eyes of every painter. I know how they whisper. They think this is my form of craziness—all artists have one don’t they? I ignore them and I keep looking. I look for the one who would be me.

sk

Sophfronia Scott is author of the novel All I Need To Get By and of Doing Business by the Book. Her work has been published in Time, People, More, Chicken Soup for the African American Woman's Soul, Forty Things to Do When You Turn Forty, and O, The Oprah Magazine. She is currently a masters candidate in fiction at the Vermont College of Fine Arts.